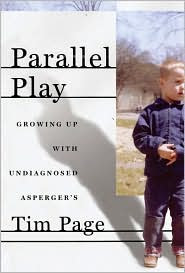

In researching Asperger's syndrome, which is the central focus of Tim Page's new memoir of childhood, Parallel Play, I found a lot of conjectural lists of famous people who may have had this condition, along with evidence to support the conjecture: it took Leonardo 12 years to paint the Mona Lisa's lips; Louis IV, king of France, bathed once a year; Bill Gates's first invention, Traff-o-Data, was a device that counted the number of cars passing a point in a road; George Washington so feared being buried alive that he ordered that his body be laid out three days prior to burial, so as to make sure he was really dead. There are also apparently confirmed cases of Asperger's among notable living people, including Dan Aykroyd, Satoshi Tajiri (creator of Pokemon), and Steven Spielberg.

In researching Asperger's syndrome, which is the central focus of Tim Page's new memoir of childhood, Parallel Play, I found a lot of conjectural lists of famous people who may have had this condition, along with evidence to support the conjecture: it took Leonardo 12 years to paint the Mona Lisa's lips; Louis IV, king of France, bathed once a year; Bill Gates's first invention, Traff-o-Data, was a device that counted the number of cars passing a point in a road; George Washington so feared being buried alive that he ordered that his body be laid out three days prior to burial, so as to make sure he was really dead. There are also apparently confirmed cases of Asperger's among notable living people, including Dan Aykroyd, Satoshi Tajiri (creator of Pokemon), and Steven Spielberg.Early on, in one of the very best descriptions I've come across of the way the Aspie minds works, Page writes of himself as a child:

"Caring for inanimate objects came easily. Learning to make connections with people -- much as I desperately wanted to -- was a bewildering process, for they kept changing.... Not only did I not see the forest for the trees; I was so intensely distracted that I missed the trees for the species of lichen on their bark."

He proceeds to document this social impediment in hilarious, excruciating, and sometimes moving anecdotes. The book reproduces a stick drawing he did of himself when he was 11, and you would swear the artist couldn't have been more than 5, so primitive is the rendering. Not only that, but this scarecrow is under attack from a bomb, TNT, a knife, a bullet, a grenade, and a rattlesnake, even though his word balloon says, "Everyone loves me" and he is wearing a crown. At the age of 3, he found the death of his grandfather so profoundly upsetting that he became obsessed with the idea of mortality. His first autobiography, written at age 9, he calls "a decidedly curious few pages devoted almost exclusively to the losses I had sustained."

If you read Page's piece in The New Yorker a couple of years ago, that may be all you need. Like more and more books these days, this one is pretty short and feels truncated -- you may expect a fuller picture of the author's more recent life than the one sketched here. But if you didn't read the magazine piece and you are at all curious about this increasingly recognized condition, or why your neighbor won't meet your eyes, or some people enjoy routine so much, then...well, then, you might also like to know -- as Tim Page himself might tell you, with his admirable humor and self-awareness -- that the galleys of Parallel Play measure exactly 8 1/2 by 5 1/2 inches.

To read the full review, follow the link in this post's title.

No comments:

Post a Comment